Shotgun Ballistics

Shotgun Ballistics

This article answers a reader’s question and discusses shotgun ballistics.

“What about Shotguns and Shotgun Ballistics? The entire Ballistics Series was great and it was the first time that the science behind shooting was explained in a way that made sense. I’m considering a shotgun for home defense, so could you cover Shotgun Ballistics in one of your upcoming articles? Thank you.” – Brian in Temecula

Brian, thank you for the e-mail and for the opportunity to give the venerable shotgun the attention it deserves. Although there are many similarities between shotgun ballistics and rifle/pistol ballistics, the differences are significant enough to focus solely on the shotgun. What makes shotguns unique among other firearms is the wide variety of projectiles that can be fired from the same platform. This includes everything from a slug and a sabot round through buck shot, bird shot, and a number of less-than-lethal options. Since slugs and sabot projectiles are single solid projectiles, their ballistic characteristics are very similar to the pistol and rifle projectiles covered in the Ballistics Series. Therefore, I will focus the majority of this article on buckshot and birdshot.

Internal Ballistics

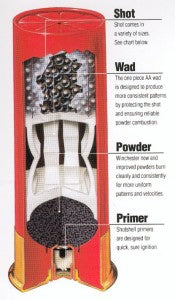

If you recall, our discussion on internal ballistics focused on the characteristics of the firearm, the cartridge, and the initial actions in the firing sequence that occur within the confines of the firearm. For this discussion, we’ll start with the cartridges, known as shot shells, and their components

Primer – similar to rifles and pistols, the shot shell primer is a small metal cup that contains an explosive mixture that, when struck by the firing pin, sends a small flame through the base to ignite the propellant.

Primer – similar to rifles and pistols, the shot shell primer is a small metal cup that contains an explosive mixture that, when struck by the firing pin, sends a small flame through the base to ignite the propellant.

Base – brass, steel, or aluminum, the base is a multi-function element that houses the primer, binds the hull, and provides rigidity to interact with the extractor and ejector to ensure firearm function.

Hull – polymer, plastic, or paper, the hull ensures the proper functioning of the shot shell by holding the individual components together behind a crimp. Once the propellant is ignited, the hull expands to the diameter of the chamber and ensures a sufficient gas seal to send the wad and shot forward.

Propellant – similar to rifles and pistols, the propellant, once ignited, produces the gas expansion required to fire the projectile(s).

Wad – Different from rifles and pistols, a shot shell requires a wad in order to: (1) provide a small internal compartment to contain the propellant and keep it separate from the shot or projectile; and (2) provide a buffer that absorbs shock and minimizes deformation of the shot as it accelerates from rest to initial velocity.

Shot – From a collection of very small to large lead or steel pellets through slugs, sabots, or less-than-lethal projectiles, the shot is a single or group of projectiles delivered from the firearm to the target.

GAUGE AND CHAMBER

Whereas rifles and pistols are designated by the caliber of the projectiles they fire, shotguns are designated by the shotshell gauge. While most shooters have heard the common gauges of 12, 20, 28, and .410, few know the origin of the term. A shotgun’s gauge is determined by the number of round projectiles of equal diameter that can be subdivided from one pound of lead. For example, a 12-gauge barrel was designed around the fact that one pound of lead could be divided into twelve 0.727-inch lead balls. The same methodology is true from the 4 gauge down to the 28 gauge. .410 is the exception to the rule since it was simply a determination of the diameter of the bore in fractions of an inch.

Whereas rifles and pistols are designated by the caliber of the projectiles they fire, shotguns are designated by the shotshell gauge. While most shooters have heard the common gauges of 12, 20, 28, and .410, few know the origin of the term. A shotgun’s gauge is determined by the number of round projectiles of equal diameter that can be subdivided from one pound of lead. For example, a 12-gauge barrel was designed around the fact that one pound of lead could be divided into twelve 0.727-inch lead balls. The same methodology is true from the 4 gauge down to the 28 gauge. .410 is the exception to the rule since it was simply a determination of the diameter of the bore in fractions of an inch.

While the gauge determines the inside diameter of the bore, the chamber designation determines the maximum length of the cartridge. Most shotguns can chamber a cartridge of either 2-3/4 inches or 3 inches while others can handle a 3-1.2 inch shell. Together, the gauge and chamber determine the maximum volume of shot or size of the projectile.

SHOT

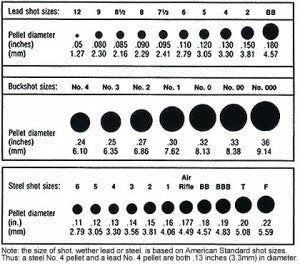

Whether lead, steel, or another material, the shot is a volume of small diameter round projectiles. In the preceding section, we discussed how the gauge and chamber determine the maximum volume of shot a cartridge can contain, the diameter of the shot itself will determine how many projectiles can fill that volume. Ranging from #12 shot (at 0.05 inches per ball) to OOO, or triple-ought (at .36 inches per ball), each have their own application. Skeet shooters engaging fast-crossing targets at close range desire a large quantity of small pellets, so they typically choose a #9 shot.

Whether lead, steel, or another material, the shot is a volume of small diameter round projectiles. In the preceding section, we discussed how the gauge and chamber determine the maximum volume of shot a cartridge can contain, the diameter of the shot itself will determine how many projectiles can fill that volume. Ranging from #12 shot (at 0.05 inches per ball) to OOO, or triple-ought (at .36 inches per ball), each have their own application. Skeet shooters engaging fast-crossing targets at close range desire a large quantity of small pellets, so they typically choose a #9 shot.

Conversely, trapshooters engage targets moving quickly away from the shooting position, so they choose either a #8 or a #7.5 shot with the requisite momentum to catch-up to and break the clay pigeon. The smaller shot is ideal for breaking clay pigeons or taking-down game birds without destroying their feathers or meat, but the small shot retains insufficient energy to take-down a larger game animal or subdue a felon. In these cases, the larger buckshot, slug, or sabot is chosen.

INTERNAL/EXTERNAL BALLISTICS – SMOOTH-BORE, FORCING CONE, AND CHOKES

Break-open, pump, and semi-automatic shotguns share the same cycle of operations and functions as the rifles and pistols I covered in Internal Ballistics – Part I. Very briefly, as the firing pin strikes the primer, a small flame is sent through the base and into the hull, which ignites the propellant. The resulting rapid gas expansion pushes the plastic hull against the inside of the chamber causing a seal from which the wad and its contents can only push forward down the bore.

Shotguns, however, differ from pistols in rifles in three main areas: smooth-bore, forcing cone, and chokes. While some shotguns are manufactured with rifled bores, many more are manufactured with smooth bores. The rifled bore is designed primarily for the rifled slug and sabot rounds and produces the gyroscopic stability required to send the projectile to the intended target. Technically, birdshot and buckshot can be fired through a rifled bore, but the rifling will “spin” the plastic wad which will translate the centrifugal force to the shot and open the shot column into a “V,” leaving a large gap in the center of the shot spread. Therefore, birdshot and buckshot are meant to be fired through smooth-bores.

Since the chamber is larger than the bore, something needs to gradually “step-down” from the hull diameter to the inside diameter of the bore. This is the forcing cone. The length and shape of the forcing cone will affect the efficiency of the wad and shot traversing the length of the barrel. Too-short of a forcing cone can exert undue stress on the lead shot and cause deformation while too-long of a forcing cone may not generate enough pressure for sufficient initial velocity.

Since the chamber is larger than the bore, something needs to gradually “step-down” from the hull diameter to the inside diameter of the bore. This is the forcing cone. The length and shape of the forcing cone will affect the efficiency of the wad and shot traversing the length of the barrel. Too-short of a forcing cone can exert undue stress on the lead shot and cause deformation while too-long of a forcing cone may not generate enough pressure for sufficient initial velocity.

Once the wad and the shot exit the barrel, the volume of shot expands in both length and width. The size of the shot, shape of the forcing cone, and constriction provided by the choke work together and determine how much the shot column spreads as it travels down-range. As this shot column passes through a two-dimensional plane at any distance, it leaves a pattern. The following graphic demonstrates the spread of the shot pattern at different distances.

Similar to the previous discussion of matching the shot size and quantity to match different applications, shotguns incorporate a choke at the end of the barrel to further affect the characteristics of the shot column as it travels to target. Returning to the skeet and trapshooting example. Skeet shooters engaging the same fast-crossing targets tend to hit their targets at a distance of roughly 25-30 yards. Using the #9 shot to maximize the number of pellets in the shot column, they also typically want the widest spread possible and choose a “wide” choke. Conversely, the trapshooters who are engaging a target going-away from them, choose the heavier #8 or #7.5 shot to hit their targets which are between 45 and 60 yards away. As such, they want a narrower and more “focused” shot column and choose a “tighter” choke.

Similar to the previous discussion of matching the shot size and quantity to match different applications, shotguns incorporate a choke at the end of the barrel to further affect the characteristics of the shot column as it travels to target. Returning to the skeet and trapshooting example. Skeet shooters engaging the same fast-crossing targets tend to hit their targets at a distance of roughly 25-30 yards. Using the #9 shot to maximize the number of pellets in the shot column, they also typically want the widest spread possible and choose a “wide” choke. Conversely, the trapshooters who are engaging a target going-away from them, choose the heavier #8 or #7.5 shot to hit their targets which are between 45 and 60 yards away. As such, they want a narrower and more “focused” shot column and choose a “tighter” choke.

From “wide” to “tight” chokes range from: Cylinder, Improved Cylinder, Skeet, Improved Skeet, Modified, Improved Modified, Light Full, Full, and Extra Full. Some shotgun barrels are “fixed” since the choke is part of the barrel construction while others are threaded for “screw-in” chokes.

External Ballistics

If you recall from the Ballistics Series, the math and physics that govern rifle and pistol projectiles provided enough information to gain a sufficient understanding to accurately predict flight to target. While there is plenty of math and physics behind shotgun ballistics, it is a lot more complicated because spheres have a very poor ballistic coefficient. It would be difficult enough to characterize the trajectory of one sphere of a given mass and initial velocity, but the interaction of hundreds of spheres traveling together renders predictable flight to a matter of generalizations. In general, the shot column centers on a core of pellets in a dense group which gradually opens in length and width. Outside of this core are pellets that begin to stray somewhat independently. Smaller pellets possess less mass and are more prone to dispersion, whereas the larger pellets with greater mass are less prone. Remember also, lead is malleable and can easily be misshapen during the firing process. The violent acceleration from zero to initial velocity may deform many pellets. Wad composition and lead density play a significant role in reducing inadvertent deformation.

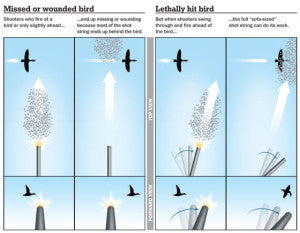

OK… enough physics. What makes shotgun shooting unique is the fact that a shot column travels to the target instead of a single solid projectile (with the exception of a slug or sabot, of course). In order to successfully engage a target with a shotgun, the shooter must hit the target with any part of the shot column. Obviously, greater success comes from hitting the target with the center of the shot column than the periphery. In order to engage a moving target with a shotgun, the shooter must not only establish a sufficient lead to match the target’s range, direction, and speed… the shooter must also follow-through and keep the shotgun moving in that direction and speed. This “influences” the shot column and “steers” both the head and tail of the column in the direction of the target.

OK… enough physics. What makes shotgun shooting unique is the fact that a shot column travels to the target instead of a single solid projectile (with the exception of a slug or sabot, of course). In order to successfully engage a target with a shotgun, the shooter must hit the target with any part of the shot column. Obviously, greater success comes from hitting the target with the center of the shot column than the periphery. In order to engage a moving target with a shotgun, the shooter must not only establish a sufficient lead to match the target’s range, direction, and speed… the shooter must also follow-through and keep the shotgun moving in that direction and speed. This “influences” the shot column and “steers” both the head and tail of the column in the direction of the target.

Terminal Ballistics

A shotgun’s range to target is a matter of each pellet’s velocity and mass. As we’ve discussed previously, round projectiles have poor ballistic coefficients and it is very difficult to measure the initial velocity of a shot column compared to the exact measurements we can collect from pistol and rifle projectiles. In general terms, #9 shot has a maximum range of about 175 yards and OO buckshot has a maximum range of about 748 yards. However, maximum range does not equate to EFFECTIVE range. These distances only describe how far the shot column can travel. If engaging a game animal or felonious assailant, the distances must be much shorter.

A shotgun’s range to target is a matter of each pellet’s velocity and mass. As we’ve discussed previously, round projectiles have poor ballistic coefficients and it is very difficult to measure the initial velocity of a shot column compared to the exact measurements we can collect from pistol and rifle projectiles. In general terms, #9 shot has a maximum range of about 175 yards and OO buckshot has a maximum range of about 748 yards. However, maximum range does not equate to EFFECTIVE range. These distances only describe how far the shot column can travel. If engaging a game animal or felonious assailant, the distances must be much shorter.

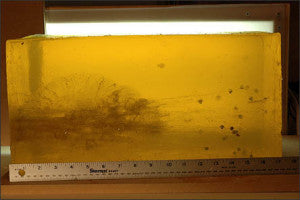

When considering personal defense, recall that in addition to shot placement, penetration and permanent wound cavity determine your ability to stop the threat. If you recall from Terminal Ballistics – Part II, extensive FBI testing concluded that adequate terminal ballistic effect takes place when expansion is combined with 12 inches of penetration. Thanks to the staff at “The Truth About Guns,” we can observe the effects of different shot types in ballistic gelatin.

#8 BIRDSHOT –

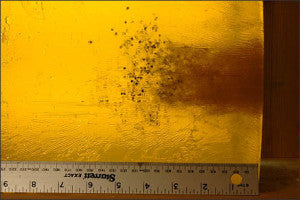

With approximately 460 #8 pellets fired from a 12 gauge shotgun into ballistic gelatin, we can see a significant permanent wound cavity, but only 4.5 to 5 inches of penetration. While this would cause a significant wound, it would most likely not provide the penetration to instantaneously end the threat.

With approximately 460 #8 pellets fired from a 12 gauge shotgun into ballistic gelatin, we can see a significant permanent wound cavity, but only 4.5 to 5 inches of penetration. While this would cause a significant wound, it would most likely not provide the penetration to instantaneously end the threat.

#4 BUCKSHOT –

Fired from the same 12 gauge shotgun, we can see that these roughly 27 pellets cause a narrower but deeper permanent wound cavity and penetrate to about 14.5 inches. Using FBI ballistics testing as a standard, this penetration is sufficient to cause instantaneous incapacitation.

Fired from the same 12 gauge shotgun, we can see that these roughly 27 pellets cause a narrower but deeper permanent wound cavity and penetrate to about 14.5 inches. Using FBI ballistics testing as a standard, this penetration is sufficient to cause instantaneous incapacitation.

OO BUCKSHOT –

OO BUCKSHOT –

With 9 pellets traveling at around 1,300 feet per second, we can see a significant permanent wound cavity, relatively wide spread, and deep penetration of about 20 inches. In many ways, this is more than adequate for hunting and personal defense.

Conclusion

Whether for sporting, competition, hunting, or personal defense, the shotgun is one of the most versatile firearms. I’ve been competing in skeet, trap, 5-stand, and sporting clays for 20 years and have thoroughly enjoyed the pace and excitement of knocking fast-moving targets out of the air and getting the instant feedback on every shot compared to the delay between shots fired and scoring in bulls-eye and long range rifle matches.

Whether for sporting, competition, hunting, or personal defense, the shotgun is one of the most versatile firearms. I’ve been competing in skeet, trap, 5-stand, and sporting clays for 20 years and have thoroughly enjoyed the pace and excitement of knocking fast-moving targets out of the air and getting the instant feedback on every shot compared to the delay between shots fired and scoring in bulls-eye and long range rifle matches.

But, which is best for personal defense? There are many considerations and trade-offs. Some consider birdshot to be a safer home defense round since buckshot can penetrate walls with sufficient energy or maximum range of nearly 750 yards to injure bystanders. However, since the purpose of employing a firearm in personal defense is a last resort and meant to instantaneously incapacitate to end a felonious assault, I believe we’ve demonstrated birdshot’s insufficient penetration is a limiting factor. Having said that, I believe the evidence supports #4 through OO buckshot for 12 gauge shotguns and either #4 or #3 buckshot for 20 gauge shotguns used in home or personal defense. As in all things firearms related, it is up to you to study the characteristics and match the right firearm and ammunition combination to match your own personal security considerations and needs.

Brian, I hope this answered your question and shed some light on the topic of shotgun ballistics.

I truly enjoy the dialogue and answering reader’s questions. If you have one, please send it to HHall@aegisacademy.com

Until then, stay safe and shoot straight.

– Howard Hall

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Staff Articles

Home Defense - What you can do...

Gun Review: Sig Sauer P938

OO BUCKSHOT –

OO BUCKSHOT –

Howard Hall

Author